'I must take my chances:' Letters Home Tell Tale of Williamstown WWI VeteranBy Stephen Dravis, iBerkshires Staff

01:28AM / Sunday, November 11, 2018 | |

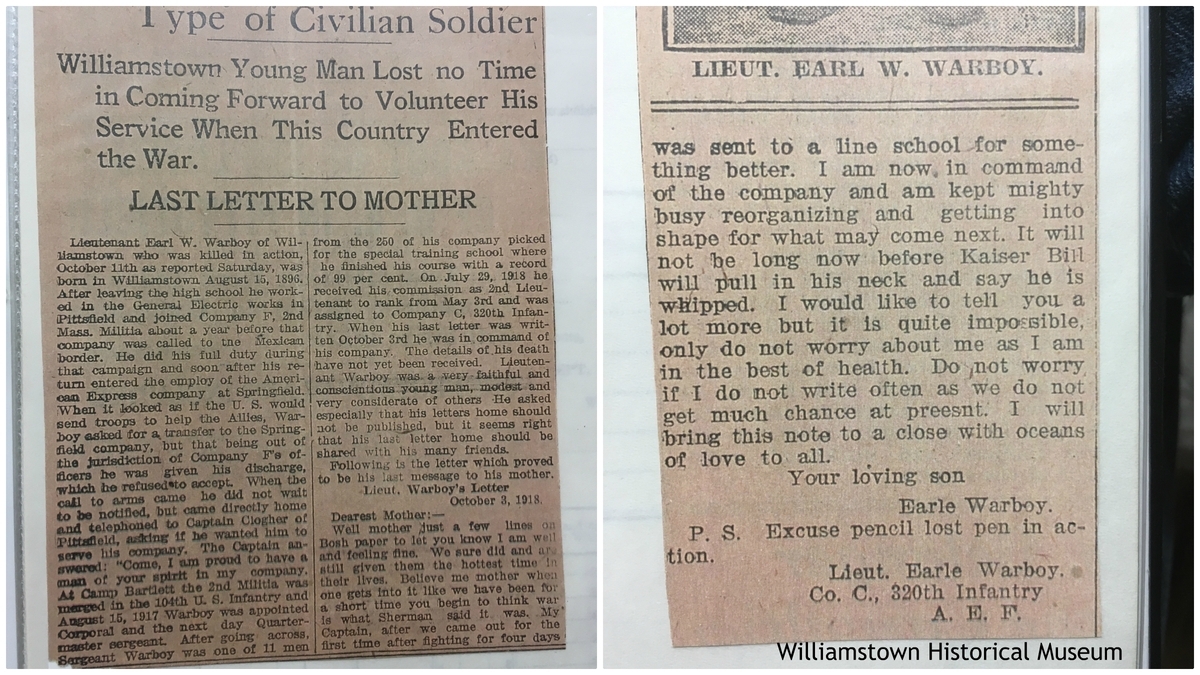

A newspaper clipping reporting the death of Williamstown resident Earl W. Warboy, who was killed in October 1918. The newspaper account includes a reprint of his Warboy's last letter home. A newspaper clipping reporting the death of Williamstown resident Earl W. Warboy, who was killed in October 1918. The newspaper account includes a reprint of his Warboy's last letter home. |

WILLIAMSTOWN, Mass. — Maybe it was because of his intended audience, maybe it was because the armistice was signed, the hostilities had ceased and Earle Olmstead Brown could begin processing his time in the trenches of World War I, or maybe it was because, as he noted, "Censorship rules are very lenient now."

But for whatever reason, Brown's Nov. 24, 1918, letter from France to his family in Williamstown had different, darker tone than what came before.

"I will never forget my first experience under shell fire," Brown wrote. "I could hear the shells whistle over my head. It gave me a queer sensation. It seemed as if I ought to be able to see them going through the air.

"At first, I was not very much afraid of them, but as time went on and they broke closer to me, I grew more bashful of them. That is the experience of every man. The longer he stays under shell fire, the worse he becomes. He does not get accustomed to them. It is the opposite feeling."

Brown's words come to us today in a documentary made by his great-granddaughter, Paige Martin, who, as a high school student in 2005, read aloud from the family's letters on a recording preserved and available for contemporary audiences at the Williamstown Historical Museum.

Through nearly two dozen vignettes spanning his spring 1918 departure across the Atlantic through his return in January 1919, Brown talks about everything from his enthusiasm for the cause to his longings for the comforts of home.

Most of the letters, addressed to his mother, are optimistic and reassuring. Even when he is twice hospitalized -- once for illness and once for a wound sustained in battle -- Brown strives to make sure his mother knows that he is OK.

But on Nov. 24, he notes that everyone in the American Expeditionary Force is supposed to write to his or her father. "Hence the special letter to you, but it is also for the rest of the family," Brown writes.

In this missive, written 13 days after the cessation of hostilities, Brown opens up a little more about the emotions he felt on the battlefield.

"I remember one time shortly before I got hit," he writes. "We were in a wood, which was not shelled much, so all of us were taking life easy. Busbee and I were dozing away in the sun, when we heard the whiz of a shell. One can never mistake the sound. Both of us gave one bound. We were after shelter. Close behind us were some new men who had never heard the shell's whistle. They never moved. They got up and went to look where the shell had landed.

"A few weeks later, and they never bothered about where they landed but merely sought a hole to crawl into."

Brown was one of nearly 300 Williamstown residents in uniform during the Great War, as it was known at the time -- a remarkable 8 percent of the population for a town of 3,708 residents, according to the 1910 Census.

Much of what we know of their experiences in the conflict now known as World War I comes to us through letters like Brown's.

"There were far more letters than I included in the [30-minute] documentary," Martin said. "My first filter was for the date -- I wanted to get a wide range of timestamps to cover the entire time that my great-grandfather was in the war. The letters were also quite difficult to read (with the handwriting and the fading ink), so the dates at the top of each letter were an easy way to choose.

"I also wanted to create a story, so I looked for letters that had interesting tidbits about his life as a soldier. I was especially interested in the daily life of a soldier in WWI, so I looked for interesting events that were held for holidays, or information about what he did during each day. In a sense, what makes these letters so interesting to me (aside from the fact that it's my great-grandfather) is that these letters tell the story of what it was like to be a regular soldier on the front in WWI. There wasn't anything particularly special about Earle - he was just a typical American soldier in the trenches. It's pretty neat to get to read first-hand sources of what was, presumably, a pretty typical scenario for American soldiers in WWI."

Fortunately, in a time before email, text messages or even transatlantic telephones, soldiers like Brown were faithful letter writers, even when they were facing the prospect of death on a daily basis.

On the other hand, those soldiers may not have wanted to dwell on their near-death experiences when they got home.

"I never asked anybody about their war experience," Williamstown native and American Legion Post 152 historian Mike Kennedy said. "I felt, and I still feel, it affected them deeply. They don't want to talk about it because you won't believe it."

Kennedy meant that he never asked people about their war experience in a social setting -- even as a child when he watched Williamstown's World War I veterans marching in the town's Memorial Day parade.

Later in life Kennedy, a Vietnam War veteran himself, took a job as the town's veterans agent. In that role, he learned many veterans' stories and came to appreciate more than ever just how difficult it might be for a survivor of any armed conflict to talk casually about the experience.

"I know guys I worked with who were in Vietnam, and I knew them for years, but I never knew what they went through," Kennedy said. "I had one guy sitting here crying before he was done. The stuff he told me … I'm sure this goes back to the World War I guys, too.

Martin, the documentarian, confirmed that it did for her great-grandfather.

"From the sounds of things, my great-grandfather Earle did not talk about the war much," Martin said. "My grandfather didn't know much about his father's time in the war, but talking with my grandfather, I could tell that he was very proud of him. Not only did he keep all of these letters, but he also kept the piece of shrapnel that wounded Earle Sr. just before the end of the war.

"The only story my mom remembers hearing from her grandfather (Earle Sr.) about the war was this: Earle remembers one day being on the front lines and suddenly hopping up from where he was -- no idea why. At that exact instance, a bullet whizzed by where he had just been sitting. The fact that he jumped up at that moment saved his life. This seemed to have made quite an impression on him."

Kennedy explained that the trauma of fighting in a war simply can't be adequately explained to those who weren't there.

"We're fighting [the Vietnamese] in their front yard, and they can't deal with us with our jets and napalm and artillery," he said. "So they come out at night. So when you're trying to sleep, they're dropping mortar rounds on you, rockets on you. So a lot of these guys I know, they don't go to sleep until the sun comes up.

"How many people would believe that? And why would they tell you that? The guys in World War I, are they going to tell you about the rats and the lice eating them alive and the mud up to their knees? And they're bored to tears until they get into a fight."

There are moments of boredom and tedium that can be glimpsed in Brown's letters, but mostly he regaled his mother with stories of his activities, whether they be going to dances held by the YMCA or taking possession of an abandoned German supply depot: "What a time we had. Can you imagine us rummaging through those supplies? I can't begin to tell you everything."

And often, his letters were tinged by the optimism of an American confident that his country's entry would signal a swift end to the conflict.

"I am glad I am here," Brown wrote in May 1918. "I want to see the Germans get licked proper. They need it, and the U.S. is the one that will do the licking. We all feel the same way.

"Of course, I would like to be home, but I would like to see the end of the war."

And Brown did see that end. As he predicted, the Americans helped turn the tide of the war that began in July 1914 and ended with the armistice signed on Nov. 11, 1918.

In between his induction in early 1918 and the war's end, the 24-year-old faced his own mortality.

"The war is on the wane, so do not worry," Brown wrote his mother in August 2018. "Of course, I may be one of the unlucky and get knocked off at the very finish, but I must take my chances. There are more wounded than killed. At the hospital, any man with an arm or leg off, we said that was his pass to God's country. If it was merely a slight wound, it is a good one to be desired. It keeps you off the firing line for a while. One that is killed is expressed, 'Pushing up daisies.' Don't think we are heartless. We are not."

Two months later, proving that even a war "on the wane" can be lethal, Brown wrote from an Army hospital:

"Our regiment was on one of the first fronts of the war, and we were to go over and take a little more from the Huns. They gave us an artillery barrage that I will never forget. All we could do was to take our chances. You must imagine the results and realize how wonderfully lucky I was in recovering with only a slight wound. I was lying with another fellow when suddenly a bang. I felt an awful concussion on my back and a sharp burning sensation. For the next half hour, I think I was crazy. I could not calm down. My nerves simply went on strike. Do you know that a cigarette did more to quiet my nerves than anything else. Yet they claim tobacco has no value.

"The boy beside me never moved. He has done his bit."

|

MEMBER SIGN IN

MEMBER SIGN IN

MEMBER SIGN IN

MEMBER SIGN IN